Professor Wagner followed in the footsteps of Dr. Heinrich Landois, who famously wrote a comprehensive scholarly study on the voices and sounds of animals.

Professor Wagner followed in the footsteps of this scholar until he ultimately overtook him with an excellent book of his own, Acrididae: Grasshoppers and their Sound Mechanics, for which he selected a quotation from Aristotle’s History of Animals as an epigraph: “Ai akrides tois pedaliois pribousai poiosi ton psochon” (Locusts produce a sound by rubbing themselves with their legs).

He spent the next two years writing a book concerning the sounds made by houseflies (Musca domestica), in which he contradicted the assertion of his mentor, Dr. Heinrich Landois, that the individual field of audibility of the fly’s four droning apparatuses was 0.0083 millimeters. He proved that the precise limit of this field amounted to 0.00821 millimeters.

Dr. Heinrich Landois attempted to reply to him, in clownish fashion, in a pamphlet titled “0.0083 or 0.00821? A Contribution to the Sounds of Animals,” but he only dug his own grave in doing so, and when Professor Wagner published Musical Butterflies, Dr. Heinrich Landois was definitively buried as a scholar—and along with him no less notable researchers in the field than Kirby and Spence. Indeed, following the release of that book, some even spoke ill of the dead, including the great Réaumur, who had once published a book on the sound made by Acherontia atropos, containing the following abysmally unscientific sentence: “…qu’il [the sound] était produit par les frottements des tiges barbues contre la trompe” (that it [the sound] was produced by the friction of the barbed stems against the proboscis) *See: Memoires pour servir à l’histoire des insectes. Tome II. Partie II. Septième Mémoire p. 51 Amsterdam, chez Pierre Mortia 1737.

This execution of scholars both living and deceased was followed three years later by the The Chirping Apparatus of the Beetle; A General Textbook on the Sounds of Insects; and, five years later—the crown jewel of Professor Wagner’s scholarly endeavors—The Number of Oscillations in the Tones of Two-Winged Insects, in which extraordinarily important material was compiled for the scholarly community.

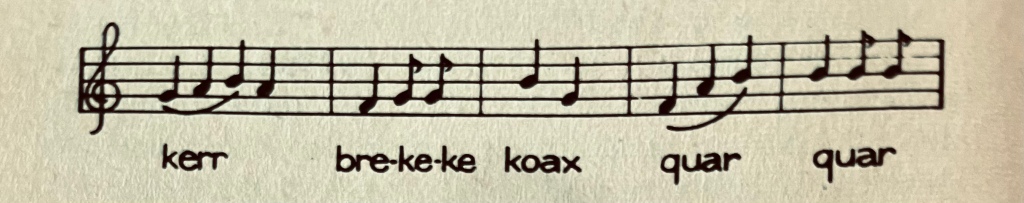

C, D, E, F, G, A, H, and indeed counter-octaves, great octaves, unbroken octaves, middle octaves, double octaves, triple octaves, quadruple octaves—for example the sound:

The majority of scholars did not understand it. On the basis of these research findings, Professor Wagner was awarded a distinguished professorship.

*

When it came to social life, Professor Wagner was no recluse. Quite the contrary. He enjoyed socializing and was very skilled at steering the conversation towards the voices of animals. It was for this reason that he inspired dread in cafes, in restaurants, in theaters, and in streetcars. Indeed, on two occasions he was even thrown out of the church, once for lecturing a grandpa on the sounds of the woodworm, and another time for explaining to a woman the sounds made by the very bug that was then crawling across her skirt.

Once, while traveling around the country for research, he arrived at an inn where he ordered himself lunch. To his astonishment, when the soup was served, he observed something moving across his plate.

“Dear friend,” he said cordially, “I have found a live beetle in this soup of yours.”

“Then it must have only just fallen in,” he was told, “otherwise it would have been cooked through.”

“I’ll grant you that,” the professor said, “but the beetle that I’ve extracted here is of a type that is not commonly found in soups. It is the burying beetle called Nicrophorus vespillo, the most common type of burying beetle. It has two black and yellow stripes on its elytra. I’ll say once more: it is not typically found in soups. In soups we tend to find flour beetles—Tenebrio molitor—every now and then the grain weevil—Calandra granaria; the shiny brown and wingless house flea—Pulex irritans—jumps into soups quite often; mosquitoes often fall into soups in the tropics, or, in our part of the world, the common housefly. In soups we find from time to time the bedbug—Acanthia lectularia—which in this case misses the mark, because lectularia, in translation, means “bed dwelling.” In the Banat, I once fished a common European scorpion—Scorpio europaeus—out of my sauce, and in those households or restaurants in which neither a hedgehog nor sulfur vapor is ready at hand, there, dear friend, you will frequently find in prepared dishes the oriental cockroach—Periplaneta orientalis. Periplemes is Greek for “running.” That’s everything that one ordinarily finds in soups, but Nicrophorus vespillo? Very, very rare. It would please me greatly to be able to educate you on the means by which burying beetles generate their sounds. Burmeister has already shown that they belong to that species of beetle that does it by means of the rubbing of the elytra. The tone is a light hum that transitions to a gentle murmur: “grujgru.”

That was the final straw for the innkeeper. He grabbed the professor by the coattails and dragged him out the door. He then threw his hat at him and shouted: “We have many an odd fellow come here for lunch, but never before has anyone made such a fuss over something so trivial.”

And the innkeeper’s sons threw rocks in the scholar’s direction.

*

“Dear boy,” miss Olga said to me, as we were reunited after three months, “I want to look out for your future, for surely you recognize that scholars engaged in research in the field of Zoomusicology enjoy special protections from the Ministry of Education.”

I did not understand.

“Do you still not know what I’m getting at?”

“No, not at all.”

“Dear boy, I wanted to marry Professor Wagner. After all, we are sensible people,” she continued, as she saw that this news was not well received by me, “and you will surely appreciate my efforts. You would have been my man friend, and I would have sung your praises to my husband until he would have been forced to take you under his wing. Unfortunately, Professor Wagner resisted my advances, and there is nothing left for you to do but hug me in my unwedded state.”

“I spent last evening in the company of Professor Wagner,” the sensible young lady explained. “You know that spot south of Hluboká, those ponds in the middle of the woods; we sat on the bank of one such pond yesterday evening. I deliberately wore no corset, to ensure that the good professor did not injure himself on the hooks. But it was all in vain. I was all over him, but do you think he was receptive? He told me all about the voices of sea slugs and snails.

As we sat there in this way, I rubbed up against him and gathered my skirt so that my stockings and garters were visible, but do you think he ceased to go on about the voices of sea slugs and snails?

‘Professor,’ I said, as it finally became too much for me to bear, ‘do you know that we are completely alone here? And do you know that there are certain girls who are in love with you?’

‘Brekekekex, koax, koax!’ the professor responded. ‘Quak, quak, quak. Krax, krekekax, klunkerlekunk! Brekekekex, koax, koax!’

I was frightened. ‘Professor!’

‘Quak, quak, quok, quuuk, quer quak!’ he replied, lost in thought.

All around us the croaking of frogs rang out.

Professor Wagner grasped my hand and said: ‘Young lady, my theory is entirely correct. The frogs begin to ribbit in the following melody.’

He drew out a scrap of paper and jotted:

‘Keep this piece of paper to remember me by,’ he continued, ‘and set it aside until you again speak of girls who are in love with me. I will send you a copy of my next book, On the Voices of Green Grass Hoppers, Rana esculenta.’

Then we returned home in silence.

What do you have to say about all that?”

“That, for once in his life, Professor Wagner has committed folly,” I replied, embracing Olga.